Overview

The Australian labour market is highly gender-segregated by industry and occupation, a pattern that has persisted over the past two decades. Australia, the UK and the OECD show broadly similar gender segregation patterns. This paper looks at the features of ‘female-dominated’ and ‘male-dominated’ organisations, while highlighting the unequal distribution of women and men across industries and occupations.

Data is sourced from the Workplace Gender Equality Agency’s (WGEA) dataset (2017-18 reporting period) [1], the Australian Bureau of Statistics’ (ABS) Labour Force Quarterly Survey (May 1998 and May 2018 periods) [2].

Table of contents

- Key findings

- International comparisons

- Gender segregation in organisations

- Remuneration in female and male dominated organisations

- Gender pay gaps in female and male dominated organisations

- Gender segregation by industry

- Gender segregation and leadership by industry

- Gender segregation by occupation

- Leadership presence across ages

- Full-time average weekly hours by occupation

- Time spent in unpaid care work

- References

Key findings

- Occupational gender segregation has remained persistent over the last 20 years.

- The proportion of women in traditionally female-dominated industries (Health Care and Social Assistance and Education and Training) has increased.

- Some male-dominated industries (Construction and Transport) recorded a decline in female representation, while others (including Mining, and Electricity, Gas, Water and Waste Services) recorded growth.

- Although men dominate in leadership roles across all industries (including female-dominated industries), women hold a substantially higher percentage of CEO and key management personnel roles in female-dominated industries.

- Average remuneration in female-dominated organisations is lower than in male-dominated organisations. However, female managers working in male-dominated organisations are more likely to earn salaries closer to their male colleagues.

- Performance pay and other additional remuneration plays a greater role in male-dominated industries, leading to higher gender pay gaps for total remuneration.

- There has been a substantial increase in the proportion of females in the male dominated Manager occupation (up from 28.3% in 1998 to 36.18% in 2018).

- On an occupational level, male-dominated workplaces have smaller proportions of part-time employees and full-time employees tend to work longer hours ‑ attributes that may deter people with family and caring responsibilities.

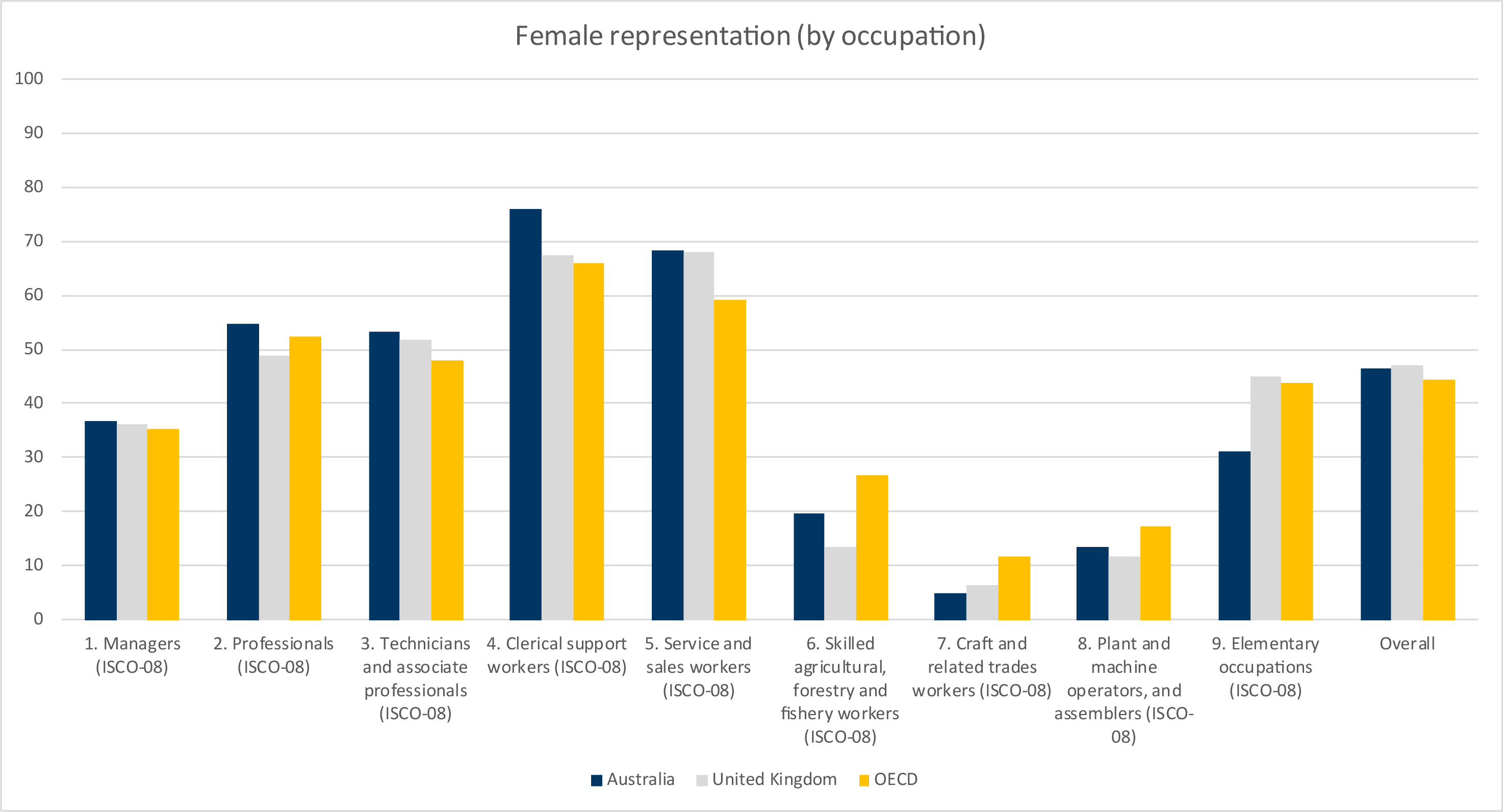

International comparisons

The Australian workforce is widely segregated by gender, however, a comparison with the UK and the OECD [3] reveals that industrial segregation is universal within this comparison group.[4]

- Notably, Australia, the UK and OECD, have very low female representation within the Craft and Related Trades and Plant and Machine Operator occupation groups. However, Australia lags behind both comparison groups in Craft and Related Trades. [5]

- Australia has a low female representation within the Skilled Agricultural, Forestry and Fishing occupation group compared with the OECD average, but is notably higher than the UK.

- Australia has low female representation among the Managers and Elementary Occupations occupational categories, with notably less female representation than the UK and OECD in the Elementary Occupations category.[6]

- Australia has very high female representation within the Clerical and Support Workers and Service and Sales Workers occupational categories. In both cases, female representation is well above 60% making these occupational categories female dominated. Within the Clerical and Support Workers occupational category, Australia’s female representation is notably higher than the UK and OECD average.[7]

Figure 1: Comparison of the female composition of occupations (by ISCO category) within Australia, the UK and the OECD [8]

Gender segregation in organisations

Table 1 breaks down the number of employees in the WGEA dataset (covering non-public sector organisations with 100 or more employees) by organisations that are classified as either:

- Female-dominated (60% or more women)

- Male-dominated (40% or less women)

- Mixed (41% to 59% women).

The data shows that the majority of Australian employees continue to work in industries dominated by one gender. Only 46.5% of employed Australians work in gender mixed organisations.

Table 1: Gender dominance across WGEA reporting organisations, 2018 [9]

|

Gender Dominance |

Female employees (No.) | Male employees (No.) | Total employees (No.) | Total employees (%) |

| Female-dominated | 792,329 | 284,246 | 1,076,575 | 25.9 |

| Mixed | 989,389 | 945,292 | 1,934,681 | 46.5 |

| Male-dominated | 302,429 | 842,655 | 1,145,084 | 27.6 |

Remuneration in female and male dominated organisations

The average base salary and total remuneration ('total remuneration' includes base salary, superannuation, performance pay, bonuses and other discretionary pay) of all full-time employees is outlined in Table 2.

An overall comparison of gender-dominated organisations shows that:

- Female employees are paid less than male employees across all gender dominant classifications.

- Employees in female-dominated organisations have lower salaries on average, for base salary and total remuneration, when compared to male-dominated organisations.

Table 2: Average full-time base salary and total remuneration by gender dominance, 2018 [10]

| Female | Male | Difference | ||||

| Gender dominance |

Average base salary ($) |

Average total remuneration ($) |

Average base salary ($) |

Average Total remuneration ($) |

Base salary ($) |

Total remuneration ($) |

| Female dominated | 81,133 | 99,324 | 96,780 | 113,633 | 15,6467 | 14,309 |

| Mixed | 76,702 | 91,099 | 95,577 | 122,840 | 18,875 | 31,741 |

| Male-dominated | 78,879 | 94,760 | 95,336 | 120,477 | 15,457 | 25,717 |

Gender pay gaps in female and male dominated organisations

Gender pay gaps across female-dominated, male-dominated and mixed organisations vary, but consistently favour men. Table 3 shows:

- Gender pay gaps in favour of men exist in female-dominated, male-dominated and mixed organisations.

- Performance pay and other additional remuneration in male-dominated industries leads to higher gender pay gaps for total remuneration.

- Female managers working in male-dominated organisations are more likely to earn salaries closer to

their male colleagues.

Table 3: Full-time gender pay gaps by gender dominance in organisations, 2018 [11]

| All Employees | Manager | Non-Managers | ||||

| Gender Dominance | Base Salary (%) | Total Remuneration (%) | GPG base salary (%) | Total remuneration (%) | Base salary (%) | Total remuneration (%) |

| Female-dominated | 13.2 | 15.0 | 16.5 | 18.3 | 10.0 | 11.7 |

| Mixed | 18.9 | 23.4 | 23.3 | 28.5 | 14.1 | 17.6 |

| Male-Dominated | 15.1 | 19.1 | 10.9 | 11.6 | 15.4 | 20.3 |

Note: Base salary and total remuneration exclude CEOs/Heads of Business in Australia. Total remuneration includes base salary, superannuation, performance pay, bonuses and other discretionary pay.

Gender segregation by industry

Table 4 shows the persistence of industrial gender-segregation over the last two decades. Each of the 19 industries is classified as either female-dominated, male-dominated or mixed*.

Between 1998 and 2018:

- The Health Care and Social Assistance and Education and Training industries are increasingly dominated by women.

- Many of the male-dominated industries, including Wholesale Trade, Manufacturing, Electricity, Gas and Water and Waste Services and Mining have seen an improvement in female representation.

- Declines in female representation are recorded in two male-dominated industries: Construction and Transport, Postal and Warehousing, Information Media and Telecommunications and the mixed industry: Financial and Insurance Services.

- Amongst the mixed industries, Public Administration and Safety, Rental, Hiring and Real Estate Services, and Information Media and Telecommunications in particular have become more gender balanced over the past 20 years.

Table 4: Proportion of female employees by industry, 1998 and 2018 [12]

| Industry | Female employees, 1998 (%) | Female employees, 2018 (%) | Female employees, differences (.pp) | Gender composition (2018) |

| Health Care and Social Assistance | 77.2 | 79.0 | 1.9 | Female-dominated |

| Education and Training | 65.8 | 73.2 | 7.4 | Female-dominated |

| Retail Trade | 54.4 | 55.0 | 0.6 | Mixed |

| Accommodation and Food Services | 54.5 | 54.9 | 0.4 | Mixed |

| Administrative and Support Services | 51.2 | 51.5 | 0.3 | Mixed |

| Public Administration and Safety | 41.9 | 48.6 | 6.8 | Mixed |

| Rental, Hiring and Real Estate Services | 43.1 | 48.5 | 5.4 | Mixed |

| Financial and Insurance Services | 57.3 | 48.1 | -9.2 | Mixed |

| Arts and Recreation Services | 47.6 | 46.4 | -1.2 | Mixed |

| Other Services | 38.0 | 43.6 | 5.6 | Mixed |

| Professional, Scientific and Technical Services | 42.5 | 43.3 | 0.9 | Mixed |

| Information Media and Telecommunications | 44.0 | 42.0 | -2.0 | Mixed |

| Wholesale Trade | 30.1 | 34.7 | 4.6 | Male-dominated |

| Agriculture, Forestry and Fishing | 30.1 | 30.1 | 0.0 | Male-dominated |

| Manufacturing | 25.9 | 29.5 | 3.6 | Male-dominated |

| Electricity, Gas, Water and Waste Services | 17.6 | 23.8 | 6.2 | Male-dominated |

| Transport, Postal and Warehousing | 23.1 | 20.9 | -2.2 | Male-dominated |

| Mining | 9.4 | 16.3 | 6.8 | Male-dominated |

| Construction | 13.8 | 12.0 | -1.8 | Male-dominated |

Note: Data is based on May as the reference period.

Note: Female-dominated: 60% women or more. Mixed: Between 41%-59% women. Male-dominated: 40% women or less.

Gender segregation and leadership by industry

Table 5 shows the proportion of Chief executive officer (CEO) and Key management personnel (KMP) positions held by women. A comparison of gender dominance reveals:

- Men hold the majority of leadership roles, even in female-dominated industries.

- However, women are substantially more likely to hold CEO or KMP roles in mixed industries and especially female-dominated industries.

Table 5: Proportion of female CEOs and KMPs, 2018 [13]

| Gender dominance | Female CEOs (%) | Female KMPs (%) |

| Female-dominated | 37.6 | 48.2 |

| Mixed | 13.5 | 28.3 |

| Male-dominated | 6.3 | 20.7 |

| All | 17.1 | 30.5 |

Note: The Chief executive officer (CEO) or equivalent is the head of business in Australia. For corporate structures with one or more relevant subsidiaries, the definition of CEO includes the head of business for each relevant subsidiary in Australia. Key management personnel (KMP) refers to those persons who have authority and responsibility for planning, directing and controlling the activities of the entity, directly or indirectly, including any director (whether executive or otherwise) of that entity.

Gender segregation by occupation

Table 6 highlights the persistence of labour market gender-segregation by occupation between 1998 and 2018.[14]

- Occupational gender-segregation has remained consistent, with the greatest improvement in the Managers occupation category, although it persists as a male-dominated occupation. The professional’s category has also seen an increase in female representation of 7.3 percentage points over the past 20 years.

- The most notable movements have been in male-dominated occupational categories where there has been a decrease in female Machinery Operators and Drivers and an increase in female Managers.

- WGEA reporting data also shows that the representation of women steadily declines with seniority so that most senior levels of management are heavily male-dominated.[15]

Table 6: Gender Composition by Occupations Over Time [16]

| Occupation | Female employees, 1998 (%) | Female Employees, 2018 (%) | Female Employees, difference (.pp) | Gender dominance (2018) |

| Clerical and Administrative Workers | 75.8 | 75.6 | -0.2 | Female-dominated |

| Community and Personal Service Workers | 67.8 | 71.4 | 3.6 | Female-dominated |

| Sales Workers | 61.1 | 60.6 | -0.5 | Female-dominated |

| Professionals | 48.1 | 55.4 | 7.3 | Mixed |

| Managers | 28.3 | 36.3 | 8.0 | Male-dominated |

| Labourers | 35.0 | 34.7 | -0.2 | Male-dominated |

| Technicians and Trades Workers | 12.2 | 15.1 | 3.0 | Male-dominated |

| Machinery Operators and Drivers | 12.1 | 9.5 | -2.5 | Male-dominated |

| Total employees | 43.5 | 47.0 | 3.5 | Mixed |

Note: Data is based on May as the reference period. Occupations are ranked from largest proportion of female employees to smallest.

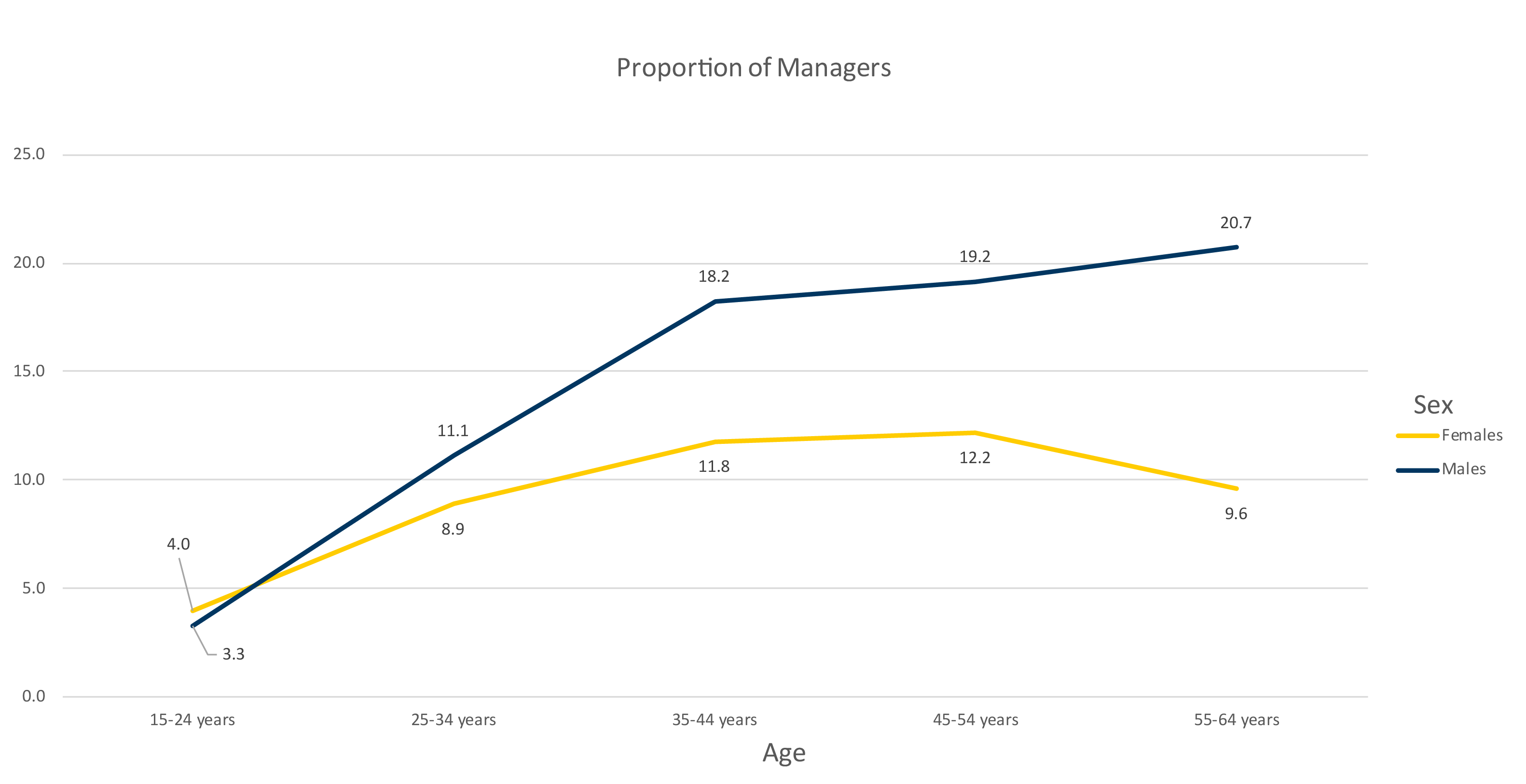

Leadership presence across ages

Figure 2 demonstrates that there is a relationship between managerial employment and age, and the experiences of men and women are different.

- The proportion of the male workforce employed in managerial occupations is higher than females for all ages except 15-24 year olds.

- The gap between the proportions of the workforce employed in managerial occupations for each gender widens with age.

Figure 2 shows the proportion of the male workforce and female workforce respectively employed in a managerial occupation at different age bands [17]

Note: Data is based on May as the reference period. Occupations are ranked from largest proportion of female employees to smallest.

Full-time average weekly hours by occupation

Table 8 below shows the average weekly hours for women and men employed full-time by occupation. The maximum weekly ordinary hours for a full-time employee is currently set at 38 hours a week.[18]

Results show that:

- Both women and men exceeded this weekly amount, working an overall average of 40.6 hours per week.

- The average for women working full-time is 38.8 hours, with men working 3.9 hours more in an average 42.7 hour week.

- Female and male managers work the most hours per week in all occupations (42.1 and 47.6 hours, respectively).

- The weekly working hours are highest in male-dominated occupations when compared to mixed and female-dominated occupations.

Table 7: Full-time average weekly hours worked by gender and occupation, 2018 [19]

| Occupation | Female (average, hours per week) | Male (average, hours per week) | Total (average, hours per week) | Gender dominance |

| Managers | 42.6 | 46.4 | 45.2 | Male-dominated |

| Machinery Operators and Drivers | 38.6 | 41.1 | 39.9 | Male-dominated |

| Technicians and Trades Workers | 37.3 | 40.6 | 40.3 | Male-dominated |

| Sales Workers | 37.3 | 42.1 | 40.0 | Female-dominated |

| Professionals | 38.6 | 41.1 | 39.9 | Mixed |

| Labourers | 37.8 | 41.1 | 40.5 | Male-dominated |

| Community and Personal Service Workers | 37.0 | 38.8 | 37.7 | Female-dominated |

| Clerical and Administrative Workers | 36.2 | 39.9 | 37.4 | Female-dominated |

| Total | 38.2 | 42.0 | 40.6 | Mixed |

Note: Data is based on May as the reference period. Occupations are ranked from largest number of total average weekly hours worked to smallest

Time spent in unpaid care work

When we look at the amount of time spent in paid work, it is important also to consider time that is spent on unpaid care work. Unpaid care work is still largely performed by women. The disproportionate amount of time women spend on unpaid care work, arguably limits women’s capacity to engage in paid work and poses barriers to entering certain occupations – contributing to the gender segregation present in the Australian workforce today.

The Household, Income, Labour and Dynamics (HILDA) survey is a source of valuable insight into the ways men and women invest their time. [20] HILDA data indicates that:

- In 2016, working age men spent 35.9 hours in paid employment and 13.3 hours on housework on average per week, 5.4 of these unpaid hours were spent directly caring for children and disabled or elderly relatives. In 2016, the average total amount of hours men spent working was 53.3 hours per week.

- In 2016, working age women spent 24.9 hours on paid employment and 20.4 hours on housework on average per week, 11.3 of these unpaid hours were spent directly caring for children and disabled or elderly relatives. In 2016, the average total amount of hours women spent working was 55.8 hours per week.

References

Reference list

- WGEA (2016), Agency reporting data, 2014-15 reporting period; WGEA & BCEC (2016), Gender Equity Insights 2016: Inside Australia’s Gender pay Gap, BCEC | WGEA Gender Equity Series. Available at: https://www.wgea.gov.au/sites/default/files/BCEC_WGEA_Gender_Pay_Equity_Insights_2016_Report.pdf

- ABS (2018), Labour Force, Australia, Detailed, Quarterly, August 2018, cat. no. 6291.0.55.003, viewed 1 December 2018, http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/mf/6291.0.55.003

- The OECD grouping is missing two of 36 countries (Canada and NZ). It is using the latest available year of data. For OECD countries, the earliest year of data used was 2015 from Chile.

- This section refers to ISCO codes which are the international standard classifications of occupations. ISCO classifications are managed by the International Labour Organization (ILO). Please note that ISCO codes are unrelated to ANZSCO codes, which are the occupational classifications set out by the Australian Bureau of Statistics More about ISCO classifications:: < https://www.ilo.org/public/english/bureau/stat/isco/>

- According to the International Labour Organization (ILO) definition: Craft and related trades workers apply specific technical and practical knowledge and skills to construct and maintain buildings; form metal; erect metal structures; set machine tools or make, fit, maintain and repair machinery, equipment or tools; carry out printing work; and produce or process foodstuffs, textiles, wooden, metal and other articles, including handicraft goods. Plant and machine operators and assemblers operate and monitor industrial and agricultural machinery and equipment on the spot or by remote control; drive and operate trains, motor vehicles and mobile machinery and equipment; or assemble products from component parts according to strict specifications and procedures.

- According to the ILO definition: The Managers occupations group includes: Chief Executives, Senior Officials and Legislators, Administrative and Commercial Managers, Production and Specialized Services Managers, Hospitality & Retail and Other Services Managers. The Elementary Occupations group involve the performance of simple and routine tasks which may require the use of hand-held tools and considerable physical effort.

- According to the ILO definition: the Clerical and Support Workers occupational category record, organize, store, compute and retrieve information, and perform a number of clerical duties in connection with money-handling operations, travel arrangements, requests for information, and appointments. The Service and Sales Workers occupational category provide personal and protective services related to travel, housekeeping, catering, personal care, protection against fire and unlawful acts; or demonstrate and sell goods in wholesale or retail shops and similar establishments, as well as at stalls and on markets.

- Source: International Labour Organisation (2019), Employees by sex and Occupation, viewed 15 April, available: <https://www.ilo.org/ilostat/faces/oracle/webcenter/portalapp/pagehierarchy/Page27.jspx?subject=EMP&indicator=EES_TEES_SEX_OCU_NB&datasetCode=A&collectionCode=YI&_afrLoop=2134184430412436&_afrWindowMode=0&_afrWindowId=1dkfnkoeje_137#!%40%40%3Findicator%3DEES_TEES_SEX_OCU_NB%26_afrWindowId%3D1dkfnkoeje_137%26subject%3DEMP%26_afrLoop%3D2134184430412436%26datasetCode%3DA%26collectionCode%3DYI%26_afrWindowMode%3D0%26_adf.ctrl-state%3D1dkfnkoeje_214>

- Source: WGEA (2018), Agency reporting data, 2017-18 reporting period.

- Source: WGEA (2018), Agency reporting data, 2017-18 reporting period.

- Source: WGEA (2018), Agency reporting data, 2017-18 reporting period.

- Source: ABS (2018), Labour Force, Australia, Detailed, Quarterly, August 2018, cat. no. 6291.0.55.003, viewed 27 November 2018, http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/mf/6291.0.55.003

- Source: WGEA (2018), Agency reporting data, 2017-18 reporting period.

- ABS (2018), Labour Force, Australia, Detailed, Quarterly, August 2018, cat. no. 6291.0.55.003, viewed 27 November 2018, http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/mf/6291.0.55.003

- WGEA (2018), Australia’s gender equality scorecard. Available: https://www.wgea.gov.au/sites/default/files/2017-18-gender-equality-scorecard.pdf

- Source: ABS (2018), Labour Force, Australia, Detailed, Quarterly, August 2018, cat. no. 6291.0.55.003, viewed 19 November 2018, http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/mf/6291.0.55.003

- Source: ABS (2018), Labour Force, Australia, Detailed, Quarterly, August 2018, cat. no. 6291.0.55.003, viewed 19 November 2018, http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/mf/6291.0.55.003

- National Employment Standard/Australian Fair Pay and Conditions Standard (the Standard). http://www.fairwork.gov.au/employment/hours-of-work/pages/default.aspx

- Source: ABS (2018), Labour Force, Australia, Detailed, Quarterly, August 2018, cat. no. 6291.0.55.003, viewed 11 December 2018, http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/mf/6291.0.55.003

- The Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia Survey: Selected Findings from Waves 1 to 16, <https://melbourneinstitute.unimelb.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0009/2874177/HILDA-report_Low-Res_10.10.18.pdf>

Download the PDF version of this research:

Gender Segregation in Australia's Workforce (PDF, 518.72 KB)

This paper looks at the features of ‘female-dominated’ and ‘male-dominated’ organisations, while highlighting the unequal distribution of women and men across industries and occupations.